🦈#2 Mystic Founders - Thoughts on WeWork; Questions with Alexander Fitzgerald, Cuckoo CEO

Mission🚀

I’m Shaun Sharkey, founder of Faint Spectacles. ‘Faint Spectacles’ refers to the fleeting character of the digital age: an age where grand ideas, technologies and startups form, dissolve and reform at rapid speed.

We try to make some sense of some of it, with a focus on past and present.

Subscribe below :)

Eight Qs for the Founder🧠

Marcel Proust popularised a parlour game that asks 35 questions of an individual. Known today at the ‘Proust Questionnaire’, the survey teases out the ‘true inner-self’ of the subject. Founders are busy people, so we’ve cut the number of questions down to 8 instead of 35. Up this week is Alexander Fitzgerald, Founder and CEO of Cuckoo

What is your idea of perfect happiness?

A large plate of Indian food.

What is the trait you most deplore in others?

Meanness.

When and where were you happiest?

Friday Indian takeaway with the family. There's a theme here...

Which talent would you most like to have?

The ability to reply to all emails in my inbox at once with the relevant info required.

What is your most treasured possession?

My ring light.

What do you most value in your friends?

Down to earth.

What are your favourite names?

Felix. Cuckoo (sz not sz).Edmund.

Focus: Mystic Founders🔎

My first job out of university was for a startup located inside of a capitalist kibbutz, known as Old Street WeWork. Here, the formality and greyness of the corporate world were banished; instead, we were supposed to operate to a ‘new state of consciousness’: communal, non-hierarchical, relaced, and idealistic. A revolution in mode and outlook.

At least that was how the gig was billed and, initially, I took the situation at face value. After all, on my first evening, I listened to a talk on A.I. delivered by a man who looked suspiciously like Billy Connolly - I couldn’t imagine this going on inside of the towers of Slaughter and May, Citi or J.P. Morgan, therefore where else could I be but the New World?

But time passed and slowly the Utopian facade dissipated. Pleasingly, though, I realised that whilst I was not part of a daring reimagining of labour, I was amidst something far cooler: everlasting Freshers Week, funded to the tune of $300m by Masayoshi Son.

From 9am-3pm, founders, freelancers and staff of all shapes and sizes would burrow away in glass cubicles on schemes to change the world. 3pm would duly arrive and we would start to gravitate to the atrium. Ariel Pink or MGMT would be turned to volume 11. The beer would be released, for free, to all - friends were allowed in too; as many as you could get in. Huge platters of food would carousel around the floor. WeWork Community Managers’ would hawk cheap tickets to Summer Camp, where Florence and the Machine were due to headline. And then Tuesday would end and we would rock up on Wednesday, ready to do it all again.

Those heady days returned to me over the weekend, whilst watching Hulu’s new documentary: ‘WeWork: Or the Making and Breaking of a $47 Billion Unicorn’. The film captures the dreamlike strangeness of that era, when WeWork, like one of Jay Gatsby’s parties, existed as real and unreal; as a revolution in its white heat, the future an unnecessary distraction.

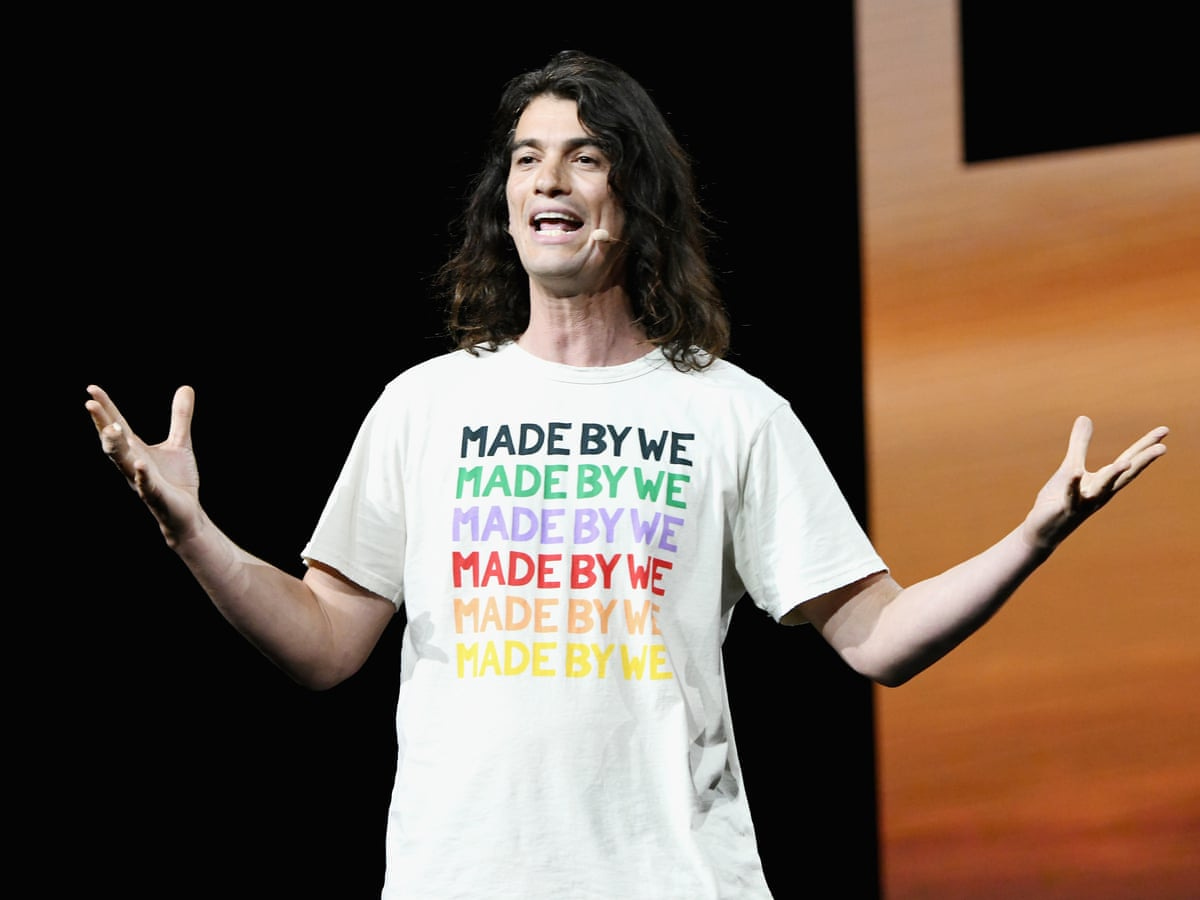

The documentary makes clear that the gaudy world of WeWork grew from the imagination and drive of the company’s founder, Adam Neumann. Neumann is a messianic figure, sheathed in countercultural affectation and world-altering rhetoric. He declares that he is vanguarding the ‘We Revolution’. Not only would his company rewrite the rules of work - it would alter daily patterns of living and in time, solve world hunger.

He looks like a festival organiser - shoulder-length shaggy hair, tall, slender, and peppy. But he is, confoundingly, a hypnotic salesperson. He barely breaks eye contact. His posture is relaxed and authoritative. He speaks fluently in the languages of vision and detail. He has the ‘reality-distortion field’ effect, originally attributed to Steve Jobs.

Silicon Valley seems to produce these sorts of founders a few times each decade. They are amalgamations of otherworldy fanaticism and capitalist steel. The 2010s had Neumann, Elizabeth Holmes and Billy McFarlane. Each, of course, was a high-profile failure. As in the WeWork documentary, many of the staff and investors who interacted with these founders understandably felt duped. The wider culture also took offence, producing a plethora of flabbergasted films, podcasts and books.

Yet I can’t shake the feeling that when another Neumann appears in the 2020s, she/he will be met with an uncritical embrace rather than healthy scepticism.

Why? On a fundamental level, Silicon Valley understands itself as a transcendental engine of social change, with the guru founder at its heart. Richard Barbrook and Andy Cameron outline in their seminal 1995 essay, The Californian Ideology, that the ideas and self-image of Silicon Valley draws from the 60s counterculture, combining the mystical with the material. Within this context, the founder is a wizard who conjures fantastical visions into the real. The Valley, by virtue of its own programming, is not inclined to doubt the likes of Neumann. Its pride and purpose are bound up with the existence of omniscient founders.

But there is also a systemic reason why the Adam Neumanns escape in-depth scrutiny. Silicon Valley is an environment where competing interests attempt to sell narratives of the future that benefits their own bottom line. For instance, a venture capitalist hundreds of millions of dollars deep into a co-working startup very much has an incentive to talk up ‘the age of collaborative working.’ A founder that is a convincing prophet is, therefore, a hyper valuable companion for the investor - they act as chief salesperson.

There is nothing sinister about narrative pushing. Both the founder and investor start out believing in the mission of the company - that’s why they are involved with the enterprise in the first place. The problem really arises when a huge quantum of diversified capital gets pulled into an oversold startup. At this juncture, that capital - and the founder - has an incentive to try and keep the music playing through to exit. This is exactly what happened with WeWork. As the wheels came off in the run up to the IPO, Neumann’s talk became more deluded and Softbank started to price its own rounds, throwing out a blizzard of positive PR.

Luckily, figures like Neumann are rare. But they do occupy an oversized portion of the collective imagination when it comes to Silicon Valley. This is a shame - the real powerhouses and changemakers in Startupland are the sober, optimistic operators like the Collinson brothers over at Stripe. They are promising - and delivering - change rooted in the real, not the preternatural. We should celebrate that more.

Concepts and Ideas📝

‘The state’ is often thought of as the antithesis of innovation: big, clunky and unable to read and respond to market signals. That, at least, is its characterisation since the 80s.

But I am very much of the view put forward by the legendary VC Bill Janeway in his work ‘Doing Capitalism in the Innovation Economy’ that it is the state that provides the platform on which the technologically revolutionary happens. Why? Innovation grows out of speculative spending - bubbles. As Janeway points out, the best example is that of the computer industry. The technological infrastructure that made the PC revolution possible in the 80s and 90s stemmed from the monumental amount of R&D spending conducted by the US government in the 50s and 60s. Check out the book here.

Emphemera🎨

David Axelrod, Barack Obama’s former Chief Strategist, interviews JP Morgan’s Chief Executive, Jamie Dimon. I was surprised at how benevolently technocratic Dimon is in his outlook. Wouldn’t make a bad president…

The Rise and Fall of Canary Wharf - Margaret Taylor

I love a good sales speech in a movie. Here are a couple of great ones - I’m an Oilman (Daniel Day Lewis, There Will be Blood); Why I earn the big bucks (Jeremy Irons, Margin Call)

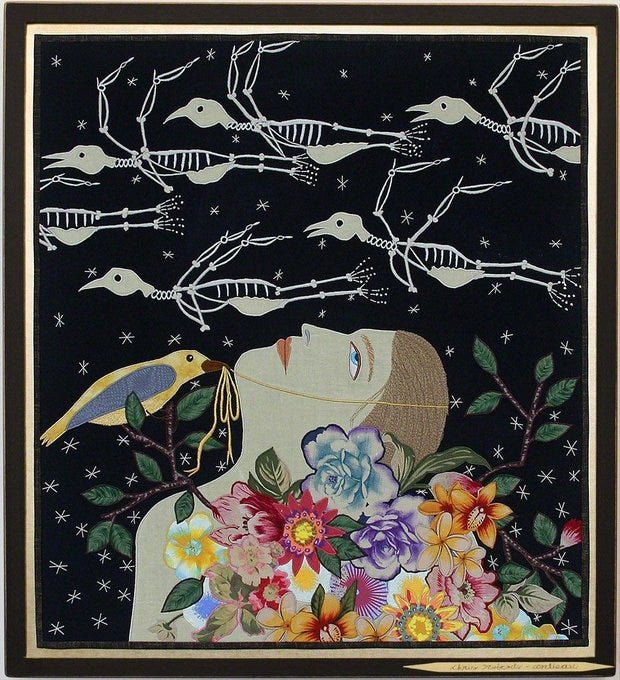

Art from Chris Roberts-Antieau - Ghosts of Birds, 2011